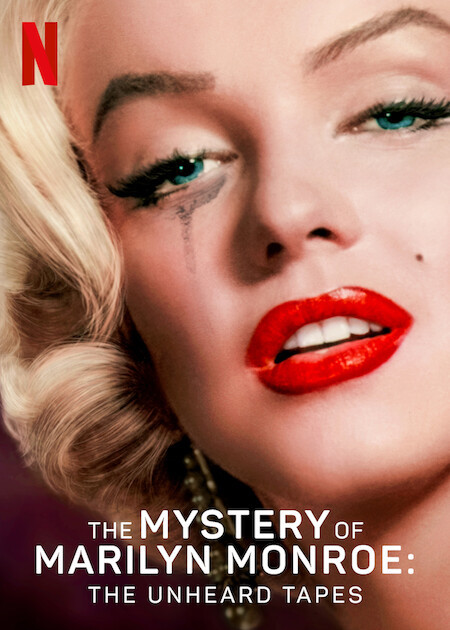

The fog around certain celebrity deaths and assassinations will perhaps never clear, but every time we get wind of some clues to these riddles, our curiosity is piqued. The examples are plenty, with, for instance, the murders of the Kennedy brothers and the killing of Lee Harvey Oswald topping the charts. Adding to these is the unusual case of the iconic American actress Marilyn Monroe, who was found dead in her bed from an overdose of barbiturates. Years after her death in 1962 at the young age of 36, there have been innumerable theories about what could have driven her to end her life at the pinnacle of her professional success, which saw her star in films including “Gentlemen Prefer Blondes,” “Seven-Year Itch,” “Some Like It Hot” and “All About Eve,” among many others that together grossed $200 million ($2 billion today). Obviously, Emma Cooper’s new Netflix documentary, “The Mystery of Marilyn Monroe: The Unheard Tapes,” must have must have got a lot of people wondering whether it would offer something new. Coming as it does ahead of Andrew Dominik’s fictionalized take on the beguiling star, Cooper’s work holds special appeal

But it does not quite quench our thirst. At the end of the documentary, we find that we have not traveled far. The troubling questions are never answered. Did she really commit suicide? Or was she pushed into taking those pills? Was she murdered? Had she become inconvenient to President John Kennedy and his brother and Attorney General Robert Kennedy? She was dating both. There was also a mafia angle.

Disappointingly, Cooper merely retells what Irish journalist Anthony Summers wrote in his 1985 biography, “Goddess.” The actress’ tragic life began with a mother who was in and out of psychiatric institutions and saw Monroe in foster care homes and orphanages. In one of them, she was definitely abused, and growing up without a father, she later chose men who were much older. There were three, but her marriages to playwright Arthur Miller and American baseball player Joe DiMaggio were highly publicized, also because the men seemed like sugar daddies. Both ended in divorce. She had a string of affairs, but the most renowned were those with the Kennedys. She was, it is said, “pimped out” by actor Peter Lawford (Rat Pack), who passed her between his two brothers-in-law, John and Robert.

Cooper’s narrative is moving in parts, even though it does not present anything dramatically new, except perhaps some lesser-known facts. Robert Kennedy visited her on the tragic night hours before an ambulance was called to take her to the hospital. Midway, she died and was brought back and placed on her bed, while he made a hasty retreat out of town.

The entire film is based on Summers’ investigation, which was commissioned by a British newspaper editor in 1982 after the Los Angeles district attorney reopened the Monroe case. The problem is that Cooper fails to step left or right to add other possible sources who might have had interesting details leading up to the “suicide.” But as the author says, he has 650 tape recordings of interviews (superbly bunched together by editor Gregor Lyon) that have never been heard before. The moot point is, do we get anything new at all in Cooper’s work